Home > Art News

The photographer Akinbode Akinbiyi wanders the winding streets of African towns telling their stories in pictures. His home town of Lagos has a special significance for him. For the last thirty years, his camera has documented the rapid development of the Nigerian megacity. His latest project will gather all his images together in a book in the same way as a ‘jazz song’.

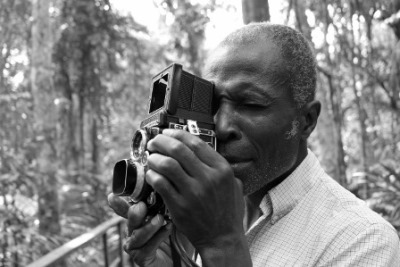

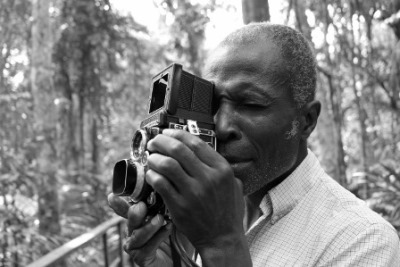

Akinbode Akinbiyi is a photographer, writer and curator, but above all he is an urban wanderer, recording the many and varied tales of towns and cities with his camera. He was born of Nigerian parents in Oxford in 1946, grew up in England and Nigeria, and has lived in Berlin since 1991. His artistic work melds the outsider eye with that of the participant. Rather than seeing himself as a ‘flâneur’ in the Baudelairian sense, he relinquishes the role of observer to enter into the scene, become part of its narrative and influence it with his understanding, ‘to jump inside the story and flow with it.’

FROM WALKING TO PHOTOGRAPHY

Akinbiyi discovered walking before photography. He was inspired by his maternal great-grandmother, who would walk from the central Lagos district of Obalende to Ikoyi to spend the day with her great-grandchildren, then walk back again in the heat. ‘That was my first inkling of the dignity of walking, of going on foot.’ It was at boarding school in England that the young Akinbiyi embarked on his own journey as a rambler. He continued to walk back in Nigeria, during his time studying English language and literature in Ibadan. However it was only while doing further studies in England and Germany that the camera came out.

Akinbiyi bought his first SLR camera in 1974, and spent the next three years teaching himself to take photographs. He was living in Heidelberg at the time and considering a doctorate in German literature. The decision to pursue photography professionally came in 1977, when he went to FESTAC (the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture) in Lagos with a friend, photographer Jide Adeniyi-Jones, and intensively documented this gathering of African artists. In 1990, Akinbiyi discovered the Rolleiflex medium-format camera. ‘The only disadvantages, which aren’t actually disadvantages at all, are that I have to develop the film myself, and there are only twelve exposures in each film.’ Although he occasionally uses colour, black and white is Akinbiyi’s favoured format. Career-defining moments have included his photo reports for Stern magazine and the arts magazine Du, the founding of the UMZANSI cultural centre in Durban, South Africa in 2003, his curatorial role for the Rencontres Africaines de la Photographie photographic biennales in Mali in 2001 and 2003, and of course his own exhibitions, in locations including Tokyo, Paris and Johannesburg, which have showcased his life-long interest in urban photography.

Akinbiyi is now planning a photo book about Lagos. His predilection for photo books is linked to his love of literature: just as one can read words, so one can also read images. ‘I actually always wanted to be a writer. I find the word writer [literally ‘putter down of script’] wonderful in German: you place the text, here or there, and you can do the same thing with pictures, as a ‘putter down of pictures.’ You can tell stories so well that way.’

ON FOOT AMONGST PEDESTRIANS

Submerged in the crowds of pedestrians, Akinbiyi treads softly through the streets. His two-eyed camera seems as much an extension of his wiry body as his robust brown leather shoes. His calm, benign demeanour is both a protective shield and an access pass, allowing his wanderings to take him into areas considered unsafe by some. As an artist, his aim is to try to remove barriers, to counteract the prevailing mood of circumscription by embracing openness.

The deeper the engagement with the surroundings, the more intense the experience at the moment of capture. Each shot is preceded by a dialogue: how close should I get to this? How far back should I pull? When photographing people, in particular, the distance at which photographer and subject can best interact must be found. For Akinbiyi, getting closer to your environment is a form of self-knowledge: ‘even when you have the subject there in front of you, you need to give something of yourself before you can fully receive them. You can’t see properly until you know yourself.’

The aim of Akinbiyi’s wanderings is to ‘get beneath the surface of things, to look for a better understanding of life on earth and the way different planes and paths intersect, the way threads come together and separate – I try to photograph all of that.’ He uses the word ‘serendipity’ to describe those moments which are not chance in the conventional sense, but the coincidence of numerous threads in one image. The chaos that is part and parcel of Lagos also has form: ‘form is everything, and form tells a story.’

IMAGE JAZZ

Just as Lagos is chaotic at first glance, Akinbiyi wants his photo book to present images jumbled together ‘like jazz, with its higgledy-piggledy staccato sounds.’ The book will collect around 120 pictures, from 1984 to the present. Akinbiyi uses his photographs to conjure an imaginary Lagos, one without temporal or spatial borders. Billposting, for example, has been banned in Lagos for years, but an older Lagos is evoked through a photo of a peeling billposter of the Nigerian musician Femi Kuti in Berlin:

‘Sometimes pictures might follow on almost chronologically, then there’s a break and there might even be pictures from somewhere else. Often you don’t notice – you think that’s Lagos too, or it could be Lagos, or Berlin, or London, or Paris, or Barcelona…you don’t know. I’ve given the places and dates, nothing more, at the end of the book. The reason is that for me, Lagos is a city that exists, but it’s also a fictional city, an imaginary city. I carry my Lagos with me everywhere. ’

An important thematic thread is the street, and in particular crossroads, hubs which connect all kinds of places, from business districts to rubble-strewn wasteland. These urban intersections could also be seen as symbols for the role of the image as a point at which numerous stories, and their multiple meanings, can coincide.

LAGOS STORIES

When Akinbiyi first started taking photographs in Lagos, in the 1980s, the mood was so charged he was often driven away from the streets. Instead, he mingled with the beach photographers on Bar Beach. A spirit of optimism followed: ‘everything was lively and chaotic.’ Acceptance of photographers has increased since those days, but photography in public spaces still demands sensitivity. There are some occasions, though – city festivals, even funerals – during which the private sphere is burst open: ‘for a moment everything is accessible.’

In Akinbiyi’s pictures, every element, down to the smallest detail, has the potential to become a protagonist in the story: passers-by, cars and buses speeding in every direction, forgotten rough sleepers, animals, buildings, bridges, goods changing hands, images. Branched electricity pylons criss-cross the city like orientation lines, drawing the exterior space into the picture too, another layer of the city’s undergrowth.

The strong presence of nature in Akinbiyi’s photos of Lagos hints at the town’s origins in the coastal marshlands, now the Lekki Conservation Centre. As the city grew, green spaces like the Ikoyi Park had to make room for residential areas. Akinbiyi’s images capture the way nature continues to thrive within urban structures, as well as the way the urban encroaches on nature. Depending on your point of view, the jungle might be a place of archaic masks or of primordial figures. The shapeless, the ambiguous and the absent acquire meaning in Akinbiyi’s images, because, he says, ‘the routes you don’t want to take can sometimes be the ones that point the way.’

LANDMARKS

The first picture in Akinbiyi’s book is of a milestone. Milestones were introduced to Nigeria by the British in the colonial era. They were placed on streets, in collaboration with the postal services, to mark spaces and make distances measureable. According to Akinbiyi, they indicate the intersections, cornerstones and boundaries of a city which you pass, consciously or unconsciously, whenever you walk routes used in previous times. ‘They’re like landmarks or cornerstones in our subconscious, very strong visual messages […] As artists we should draw attention to them. I try to expose these kinds of things subtly, to create awareness of the visual jazz.’

Just as some people can read wind, clouds and the play of light and shadow before the approach of a storm, Akinbiyi can read his surroundings through landmarks. Text, on signs, posters, shops or clothes, is of particular interest to him. It can be interpreted as an announcement of what lies ahead: ‘you can see it that way: that the text describes the city.’ He abstracts these linguistic messages about the urban landscape and uses them in the picture, ‘to represent a certain narrative. Photos are visual fragments of what we call reality, often not even a second of it, but a fraction of a second. You can see a lot in that tiny fragment, if you want to.’

Akinbiyi’s book particularly reveals the autobiographical landmarks of his own Lagos. Some of these now only survive in memory, or in deeply buried layers of the city, but all form part of the Lagos of today and of tomorrow. The pictures stand for themselves, their stories ready to be endlessly re-walked and visually re-written.

Autor: Claudia Cuadra

Copyright: Goethe-Institut Nigeria.

AKINBODE AKINBIYI €“ URBAN WANDERER FROM LAGOS

The photographer Akinbode Akinbiyi wanders the winding streets of African towns telling their stories in pictures. His home town of Lagos has a special significance for him. For the last thirty years, his camera has documented the rapid development of the Nigerian megacity. His latest project will gather all his images together in a book in the same way as a ‘jazz song’.

Akinbode Akinbiyi is a photographer, writer and curator, but above all he is an urban wanderer, recording the many and varied tales of towns and cities with his camera. He was born of Nigerian parents in Oxford in 1946, grew up in England and Nigeria, and has lived in Berlin since 1991. His artistic work melds the outsider eye with that of the participant. Rather than seeing himself as a ‘flâneur’ in the Baudelairian sense, he relinquishes the role of observer to enter into the scene, become part of its narrative and influence it with his understanding, ‘to jump inside the story and flow with it.’

FROM WALKING TO PHOTOGRAPHY

Akinbiyi discovered walking before photography. He was inspired by his maternal great-grandmother, who would walk from the central Lagos district of Obalende to Ikoyi to spend the day with her great-grandchildren, then walk back again in the heat. ‘That was my first inkling of the dignity of walking, of going on foot.’ It was at boarding school in England that the young Akinbiyi embarked on his own journey as a rambler. He continued to walk back in Nigeria, during his time studying English language and literature in Ibadan. However it was only while doing further studies in England and Germany that the camera came out.

Akinbiyi bought his first SLR camera in 1974, and spent the next three years teaching himself to take photographs. He was living in Heidelberg at the time and considering a doctorate in German literature. The decision to pursue photography professionally came in 1977, when he went to FESTAC (the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture) in Lagos with a friend, photographer Jide Adeniyi-Jones, and intensively documented this gathering of African artists. In 1990, Akinbiyi discovered the Rolleiflex medium-format camera. ‘The only disadvantages, which aren’t actually disadvantages at all, are that I have to develop the film myself, and there are only twelve exposures in each film.’ Although he occasionally uses colour, black and white is Akinbiyi’s favoured format. Career-defining moments have included his photo reports for Stern magazine and the arts magazine Du, the founding of the UMZANSI cultural centre in Durban, South Africa in 2003, his curatorial role for the Rencontres Africaines de la Photographie photographic biennales in Mali in 2001 and 2003, and of course his own exhibitions, in locations including Tokyo, Paris and Johannesburg, which have showcased his life-long interest in urban photography.

Akinbiyi is now planning a photo book about Lagos. His predilection for photo books is linked to his love of literature: just as one can read words, so one can also read images. ‘I actually always wanted to be a writer. I find the word writer [literally ‘putter down of script’] wonderful in German: you place the text, here or there, and you can do the same thing with pictures, as a ‘putter down of pictures.’ You can tell stories so well that way.’

ON FOOT AMONGST PEDESTRIANS

Submerged in the crowds of pedestrians, Akinbiyi treads softly through the streets. His two-eyed camera seems as much an extension of his wiry body as his robust brown leather shoes. His calm, benign demeanour is both a protective shield and an access pass, allowing his wanderings to take him into areas considered unsafe by some. As an artist, his aim is to try to remove barriers, to counteract the prevailing mood of circumscription by embracing openness.

The deeper the engagement with the surroundings, the more intense the experience at the moment of capture. Each shot is preceded by a dialogue: how close should I get to this? How far back should I pull? When photographing people, in particular, the distance at which photographer and subject can best interact must be found. For Akinbiyi, getting closer to your environment is a form of self-knowledge: ‘even when you have the subject there in front of you, you need to give something of yourself before you can fully receive them. You can’t see properly until you know yourself.’

The aim of Akinbiyi’s wanderings is to ‘get beneath the surface of things, to look for a better understanding of life on earth and the way different planes and paths intersect, the way threads come together and separate – I try to photograph all of that.’ He uses the word ‘serendipity’ to describe those moments which are not chance in the conventional sense, but the coincidence of numerous threads in one image. The chaos that is part and parcel of Lagos also has form: ‘form is everything, and form tells a story.’

IMAGE JAZZ

Just as Lagos is chaotic at first glance, Akinbiyi wants his photo book to present images jumbled together ‘like jazz, with its higgledy-piggledy staccato sounds.’ The book will collect around 120 pictures, from 1984 to the present. Akinbiyi uses his photographs to conjure an imaginary Lagos, one without temporal or spatial borders. Billposting, for example, has been banned in Lagos for years, but an older Lagos is evoked through a photo of a peeling billposter of the Nigerian musician Femi Kuti in Berlin:

‘Sometimes pictures might follow on almost chronologically, then there’s a break and there might even be pictures from somewhere else. Often you don’t notice – you think that’s Lagos too, or it could be Lagos, or Berlin, or London, or Paris, or Barcelona…you don’t know. I’ve given the places and dates, nothing more, at the end of the book. The reason is that for me, Lagos is a city that exists, but it’s also a fictional city, an imaginary city. I carry my Lagos with me everywhere. ’

An important thematic thread is the street, and in particular crossroads, hubs which connect all kinds of places, from business districts to rubble-strewn wasteland. These urban intersections could also be seen as symbols for the role of the image as a point at which numerous stories, and their multiple meanings, can coincide.

LAGOS STORIES

When Akinbiyi first started taking photographs in Lagos, in the 1980s, the mood was so charged he was often driven away from the streets. Instead, he mingled with the beach photographers on Bar Beach. A spirit of optimism followed: ‘everything was lively and chaotic.’ Acceptance of photographers has increased since those days, but photography in public spaces still demands sensitivity. There are some occasions, though – city festivals, even funerals – during which the private sphere is burst open: ‘for a moment everything is accessible.’

In Akinbiyi’s pictures, every element, down to the smallest detail, has the potential to become a protagonist in the story: passers-by, cars and buses speeding in every direction, forgotten rough sleepers, animals, buildings, bridges, goods changing hands, images. Branched electricity pylons criss-cross the city like orientation lines, drawing the exterior space into the picture too, another layer of the city’s undergrowth.

The strong presence of nature in Akinbiyi’s photos of Lagos hints at the town’s origins in the coastal marshlands, now the Lekki Conservation Centre. As the city grew, green spaces like the Ikoyi Park had to make room for residential areas. Akinbiyi’s images capture the way nature continues to thrive within urban structures, as well as the way the urban encroaches on nature. Depending on your point of view, the jungle might be a place of archaic masks or of primordial figures. The shapeless, the ambiguous and the absent acquire meaning in Akinbiyi’s images, because, he says, ‘the routes you don’t want to take can sometimes be the ones that point the way.’

LANDMARKS

The first picture in Akinbiyi’s book is of a milestone. Milestones were introduced to Nigeria by the British in the colonial era. They were placed on streets, in collaboration with the postal services, to mark spaces and make distances measureable. According to Akinbiyi, they indicate the intersections, cornerstones and boundaries of a city which you pass, consciously or unconsciously, whenever you walk routes used in previous times. ‘They’re like landmarks or cornerstones in our subconscious, very strong visual messages […] As artists we should draw attention to them. I try to expose these kinds of things subtly, to create awareness of the visual jazz.’

Just as some people can read wind, clouds and the play of light and shadow before the approach of a storm, Akinbiyi can read his surroundings through landmarks. Text, on signs, posters, shops or clothes, is of particular interest to him. It can be interpreted as an announcement of what lies ahead: ‘you can see it that way: that the text describes the city.’ He abstracts these linguistic messages about the urban landscape and uses them in the picture, ‘to represent a certain narrative. Photos are visual fragments of what we call reality, often not even a second of it, but a fraction of a second. You can see a lot in that tiny fragment, if you want to.’

Akinbiyi’s book particularly reveals the autobiographical landmarks of his own Lagos. Some of these now only survive in memory, or in deeply buried layers of the city, but all form part of the Lagos of today and of tomorrow. The pictures stand for themselves, their stories ready to be endlessly re-walked and visually re-written.

Autor: Claudia Cuadra

Copyright: Goethe-Institut Nigeria.

Art News

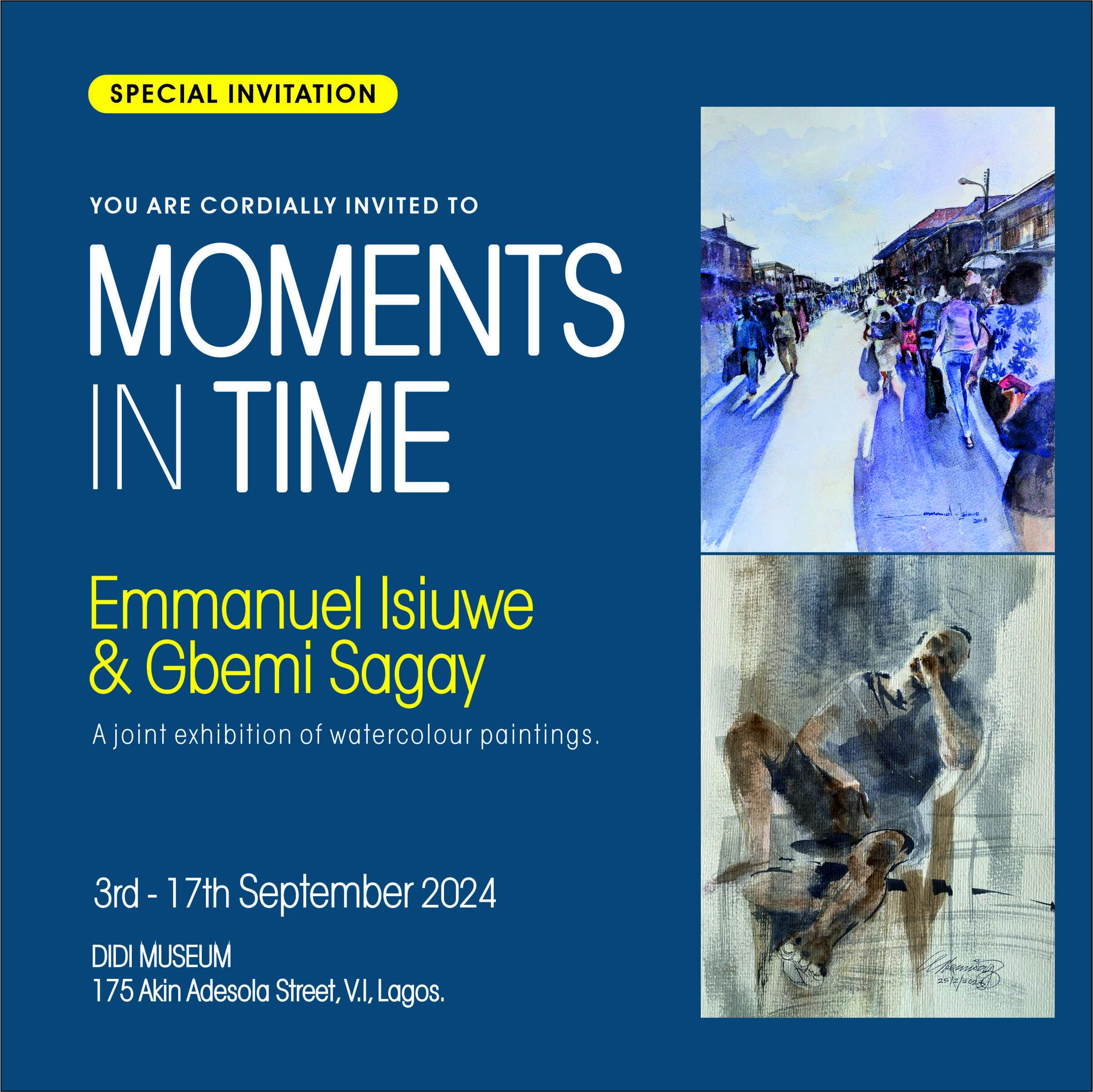

Moments in Time: A joint exhibition of watercolour paintings

Click to read...

Kunle Adeyemi Creative Art without Borders

Click to read...

Oghagbon Argungu series exhibition 10, 2024: Fieldnotes from a master

Click to read...

Metalphysics: Muraina Akeem's loud celebration

Click to read...

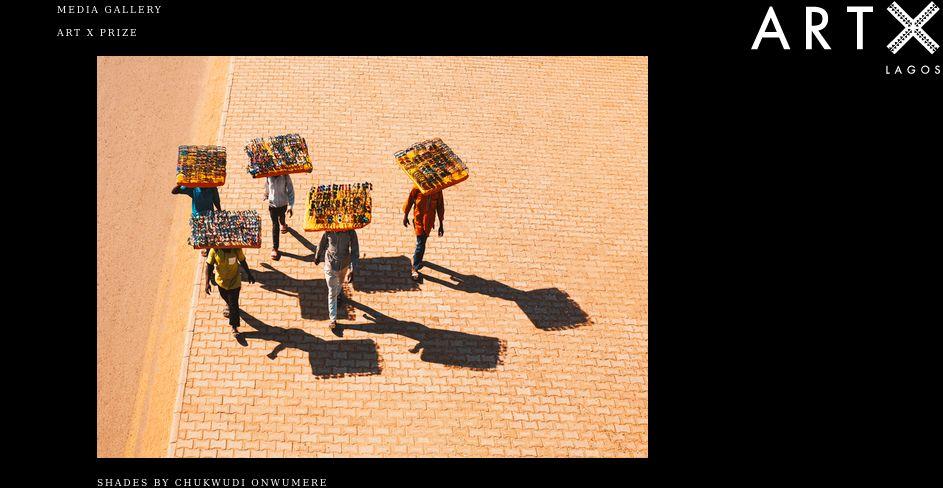

ART X Prize 2021 finalists announced

Click to read...

Art educators meet, counsel on best way to reposition visual arts in schools and the society

Click to read...

James Baldwin on the Artist’s Struggle for Integrity and How It Illuminates the Universal Experience of What It Means to Be Human

Click to read...

Fact File...Curatorial note by Ovie Omatsola

Click to read...

Page 1 of 12 [Next] [Last Page]