Home > Art News

“The Artist is no other than he who unlearns what he has learned, in order to know himself,” e.e. cummings wrote in his wonderful forgotten meditation on what he called “the agony of the Artist (with capital A).” No artist — whatever the case — has captured both the agony and the rewards of that unlearning more beautifully than James Baldwin (August 2, 1924–December 1, 1987).

In the fall of 1962, shortly after he penned his timelessly terrific essay on the creative process, Baldwin gave a talk at New York City’s Community Church, which was broadcast on WBAI on November 29 under the title “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity” — one of the most insightful and rousing reflections on the creative life I’ve ever encountered, later included in the altogether magnificent Baldwin anthology The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings.

Baldwin begins by reclaiming words which are absolutely essential to our spiritual and creative survival but which have been emptied of meaning by overuse, misuse, and abuse:

I really don’t like words like “artist” or “integrity” or “courage” or “nobility.” I have a kind of distrust of all those words because I don’t really know what they mean, any more than I really know what such words as “democracy” or “peace” or “peace-loving” or “warlike” or “integration” mean. And yet one is compelled to recognize that all these imprecise words are attempts made by us all to get to something which is real and which lives behind the words. Whether I like it or not, for example, and no matter what I call myself, I suppose the only word for me, when the chips are down, is that I am an artist. There is such a thing. There is such a thing as integrity. Some people are noble. There is such a thing as courage. The terrible thing is that the reality behind these words depends ultimately on what the human being (meaning every single one of us) believes to be real. The terrible thing is that the reality behind all these words depends on choices one has got to make, for ever and ever and ever, every day.

Baldwin’s most electrifying point is that the integrity of the artist is an analogue for the integrity of being human — the choice of the artist is a choice we each must make, in one form or another, by virtue of being alive:

I am not interested really in talking to you as an artist. It seems to me that the artist’s struggle for his integrity must be considered as a kind of metaphor for the struggle, which is universal and daily, of all human beings on the face of this globe to get to become human beings. It is not your fault, it is not my fault, that I write. And I never would come before you in the position of a complainant for doing something that I must do… The poets (by which I mean all artists) are finally the only people who know the truth about us. Soldiers don’t. Statesmen don’t. Priests don’t. Union leaders don’t. Only poets.

[…]

[This is] a time … when something awful is happening to a civilization, when it ceases to produce poets, and, what is even more crucial, when it ceases in any way whatever to believe in the report that only the poets can make. Conrad told us a long time ago…: “Woe to that man who does not put his trust in life.” Henry James said, “Live, live all you can. It’s a mistake not to.” And Shakespeare said — and this is what I take to be the truth about everybody’s life all of the time — “Out of this nettle, danger, we pluck this flower, safety.” Art is here to prove, and to help one bear, the fact that all safety is an illusion. In this sense, all artists are divorced from and even necessarily opposed to any system whatever.

In a sentiment the poet Mark Strand would come to echo in his beautiful assertion that the artist’s task is to bear witness to our experience, which is “part of the broader responsibility we all have for keeping the universe ordered through our consciousness,” Baldwin considers the singular responsibility and burden of the artist:

The crime of which you discover slowly you are guilty is not so much that you are aware, which is bad enough, but that other people see that you are and cannot bear to watch it, because it testifies to the fact that they are not. You’re bearing witness helplessly to something which everybody knows and nobody wants to face.

Just as his contemporary and intellectual peer Hannah Arendt was exploring the privilege of being a pariah, Baldwin considers the essential survival mechanism by which the artist bears his or her burden of bearing witness to the unnameable:

Well, one survives that, no matter how… You survive this and in some terrible way, which I suppose no one can ever describe, you are compelled, you are corralled, you are bullwhipped into dealing with whatever it is that hurt you. And what is crucial here is that if it hurt you, that is not what’s important. Everybody’s hurt. What is important, what corrals you, what bullwhips you, what drives you, torments you, is that you must find some way of using this to connect you with everyone else alive. This is all you have to do it with. You must understand that your pain is trivial except insofar as you can use it to connect with other people’s pain; and insofar as you can do that with your pain, you can be released from it, and then hopefully it works the other way around too; insofar as I can tell you what it is to suffer, perhaps I can help you to suffer less. Then, you make — oh, fifteen years later, several thousand drinks later, two or three divorces, God knows how many broken friendships and an exile of one kind or another — some kind of breakthrough, which is your first articulation of who you are: that is to say, your first articulation of who you suspect we all are.

With this, Baldwin turns to what art does for the human spirit — although, to borrow that wonderful phrase from Saul Bellow’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “there is no simple choice between the children of light and the children of darkness,” Baldwin argues that art’s ultimate purpose is to be an equalizer for our suffering:

When I was very young (and I am sure this is true of everybody here), I assumed that no one had ever been born who was only five feet six inches tall, or been born poor, or been born ugly, or masturbated, or done all those things which were my private property when I was fifteen. No one had ever suffered the way I suffered. Then you discover, and I discovered this through Dostoevsky, that it is common. Everybody did it. Not only did everybody do it, everybody’s doing it. And all the time. It’s a fantastic and terrifying liberation. The reason it is terrifying is because it makes you once and for all responsible to no one but yourself. Not to God the Father, not to Satan, not to anybody. Just you. If you think it’s right, then you’ve got to do it. If you think it’s wrong, then you mustn’t do it. And not only do we all know how difficult it is, given what we are, to tell the difference between right and wrong, but the whole nature of life is so terrible that somebody’s right is always somebody else’s wrong. And these are the terrible choices one has always got to make.

And yet alongside the terrible is also the terrific, if sometimes terrifying, beauty of being an artist. Echoing William Faulkner’s assertion that the artist’s duty is “to help man endure by lifting his heart,” Baldwin writes:

Most people live in almost total darkness… people, millions of people whom you will never see, who don’t know you, never will know you, people who may try to kill you in the morning, live in a darkness which — if you have that funny terrible thing which every artist can recognize and no artist can define — you are responsible to those people to lighten, and it does not matter what happens to you. You are being used in the way a crab is useful, the way sand certainly has some function. It is impersonal. This force which you didn’t ask for, and this destiny which you must accept, is also your responsibility. And if you survive it, if you don’t cheat, if you don’t lie, it is not only, you know, your glory, your achievement, it is almost our only hope — because only an artist can tell, and only artists have told since we have heard of man, what it is like for anyone who gets to this planet to survive it. What it is like to die, or to have somebody die; what it is like to be glad. Hymns don’t do this, churches really cannot do it. The trouble is that although the artist can do it, the price that he has to pay himself and that you, the audience, must also pay, is a willingness to give up everything, to realize that although you spent twenty-seven years acquiring this house, this furniture, this position, although you spent forty years raising this child, these children, nothing, none of it belongs to you. You can only have it by letting it go. You can only take if you are prepared to give, and giving is not an investment. It is not a day at the bargain counter. It is a total risk of everything, of you and who you think you are, who you think you’d like to be, where you think you’d like to go — everything, and this forever, forever.

Source: https://www.brainpickings.org

JAMES BALDWIN ON THE ARTIST’S STRUGGLE FOR INTEGRITY AND HOW IT ILLUMINATES THE UNIVERSAL EXPERIENCE OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE HUMAN

“The Artist is no other than he who unlearns what he has learned, in order to know himself,” e.e. cummings wrote in his wonderful forgotten meditation on what he called “the agony of the Artist (with capital A).” No artist — whatever the case — has captured both the agony and the rewards of that unlearning more beautifully than James Baldwin (August 2, 1924–December 1, 1987).

In the fall of 1962, shortly after he penned his timelessly terrific essay on the creative process, Baldwin gave a talk at New York City’s Community Church, which was broadcast on WBAI on November 29 under the title “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity” — one of the most insightful and rousing reflections on the creative life I’ve ever encountered, later included in the altogether magnificent Baldwin anthology The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings.

Baldwin begins by reclaiming words which are absolutely essential to our spiritual and creative survival but which have been emptied of meaning by overuse, misuse, and abuse:

I really don’t like words like “artist” or “integrity” or “courage” or “nobility.” I have a kind of distrust of all those words because I don’t really know what they mean, any more than I really know what such words as “democracy” or “peace” or “peace-loving” or “warlike” or “integration” mean. And yet one is compelled to recognize that all these imprecise words are attempts made by us all to get to something which is real and which lives behind the words. Whether I like it or not, for example, and no matter what I call myself, I suppose the only word for me, when the chips are down, is that I am an artist. There is such a thing. There is such a thing as integrity. Some people are noble. There is such a thing as courage. The terrible thing is that the reality behind these words depends ultimately on what the human being (meaning every single one of us) believes to be real. The terrible thing is that the reality behind all these words depends on choices one has got to make, for ever and ever and ever, every day.

Baldwin’s most electrifying point is that the integrity of the artist is an analogue for the integrity of being human — the choice of the artist is a choice we each must make, in one form or another, by virtue of being alive:

I am not interested really in talking to you as an artist. It seems to me that the artist’s struggle for his integrity must be considered as a kind of metaphor for the struggle, which is universal and daily, of all human beings on the face of this globe to get to become human beings. It is not your fault, it is not my fault, that I write. And I never would come before you in the position of a complainant for doing something that I must do… The poets (by which I mean all artists) are finally the only people who know the truth about us. Soldiers don’t. Statesmen don’t. Priests don’t. Union leaders don’t. Only poets.

[…]

[This is] a time … when something awful is happening to a civilization, when it ceases to produce poets, and, what is even more crucial, when it ceases in any way whatever to believe in the report that only the poets can make. Conrad told us a long time ago…: “Woe to that man who does not put his trust in life.” Henry James said, “Live, live all you can. It’s a mistake not to.” And Shakespeare said — and this is what I take to be the truth about everybody’s life all of the time — “Out of this nettle, danger, we pluck this flower, safety.” Art is here to prove, and to help one bear, the fact that all safety is an illusion. In this sense, all artists are divorced from and even necessarily opposed to any system whatever.

In a sentiment the poet Mark Strand would come to echo in his beautiful assertion that the artist’s task is to bear witness to our experience, which is “part of the broader responsibility we all have for keeping the universe ordered through our consciousness,” Baldwin considers the singular responsibility and burden of the artist:

The crime of which you discover slowly you are guilty is not so much that you are aware, which is bad enough, but that other people see that you are and cannot bear to watch it, because it testifies to the fact that they are not. You’re bearing witness helplessly to something which everybody knows and nobody wants to face.

Just as his contemporary and intellectual peer Hannah Arendt was exploring the privilege of being a pariah, Baldwin considers the essential survival mechanism by which the artist bears his or her burden of bearing witness to the unnameable:

Well, one survives that, no matter how… You survive this and in some terrible way, which I suppose no one can ever describe, you are compelled, you are corralled, you are bullwhipped into dealing with whatever it is that hurt you. And what is crucial here is that if it hurt you, that is not what’s important. Everybody’s hurt. What is important, what corrals you, what bullwhips you, what drives you, torments you, is that you must find some way of using this to connect you with everyone else alive. This is all you have to do it with. You must understand that your pain is trivial except insofar as you can use it to connect with other people’s pain; and insofar as you can do that with your pain, you can be released from it, and then hopefully it works the other way around too; insofar as I can tell you what it is to suffer, perhaps I can help you to suffer less. Then, you make — oh, fifteen years later, several thousand drinks later, two or three divorces, God knows how many broken friendships and an exile of one kind or another — some kind of breakthrough, which is your first articulation of who you are: that is to say, your first articulation of who you suspect we all are.

With this, Baldwin turns to what art does for the human spirit — although, to borrow that wonderful phrase from Saul Bellow’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “there is no simple choice between the children of light and the children of darkness,” Baldwin argues that art’s ultimate purpose is to be an equalizer for our suffering:

When I was very young (and I am sure this is true of everybody here), I assumed that no one had ever been born who was only five feet six inches tall, or been born poor, or been born ugly, or masturbated, or done all those things which were my private property when I was fifteen. No one had ever suffered the way I suffered. Then you discover, and I discovered this through Dostoevsky, that it is common. Everybody did it. Not only did everybody do it, everybody’s doing it. And all the time. It’s a fantastic and terrifying liberation. The reason it is terrifying is because it makes you once and for all responsible to no one but yourself. Not to God the Father, not to Satan, not to anybody. Just you. If you think it’s right, then you’ve got to do it. If you think it’s wrong, then you mustn’t do it. And not only do we all know how difficult it is, given what we are, to tell the difference between right and wrong, but the whole nature of life is so terrible that somebody’s right is always somebody else’s wrong. And these are the terrible choices one has always got to make.

And yet alongside the terrible is also the terrific, if sometimes terrifying, beauty of being an artist. Echoing William Faulkner’s assertion that the artist’s duty is “to help man endure by lifting his heart,” Baldwin writes:

Most people live in almost total darkness… people, millions of people whom you will never see, who don’t know you, never will know you, people who may try to kill you in the morning, live in a darkness which — if you have that funny terrible thing which every artist can recognize and no artist can define — you are responsible to those people to lighten, and it does not matter what happens to you. You are being used in the way a crab is useful, the way sand certainly has some function. It is impersonal. This force which you didn’t ask for, and this destiny which you must accept, is also your responsibility. And if you survive it, if you don’t cheat, if you don’t lie, it is not only, you know, your glory, your achievement, it is almost our only hope — because only an artist can tell, and only artists have told since we have heard of man, what it is like for anyone who gets to this planet to survive it. What it is like to die, or to have somebody die; what it is like to be glad. Hymns don’t do this, churches really cannot do it. The trouble is that although the artist can do it, the price that he has to pay himself and that you, the audience, must also pay, is a willingness to give up everything, to realize that although you spent twenty-seven years acquiring this house, this furniture, this position, although you spent forty years raising this child, these children, nothing, none of it belongs to you. You can only have it by letting it go. You can only take if you are prepared to give, and giving is not an investment. It is not a day at the bargain counter. It is a total risk of everything, of you and who you think you are, who you think you’d like to be, where you think you’d like to go — everything, and this forever, forever.

Source: https://www.brainpickings.org

Art News

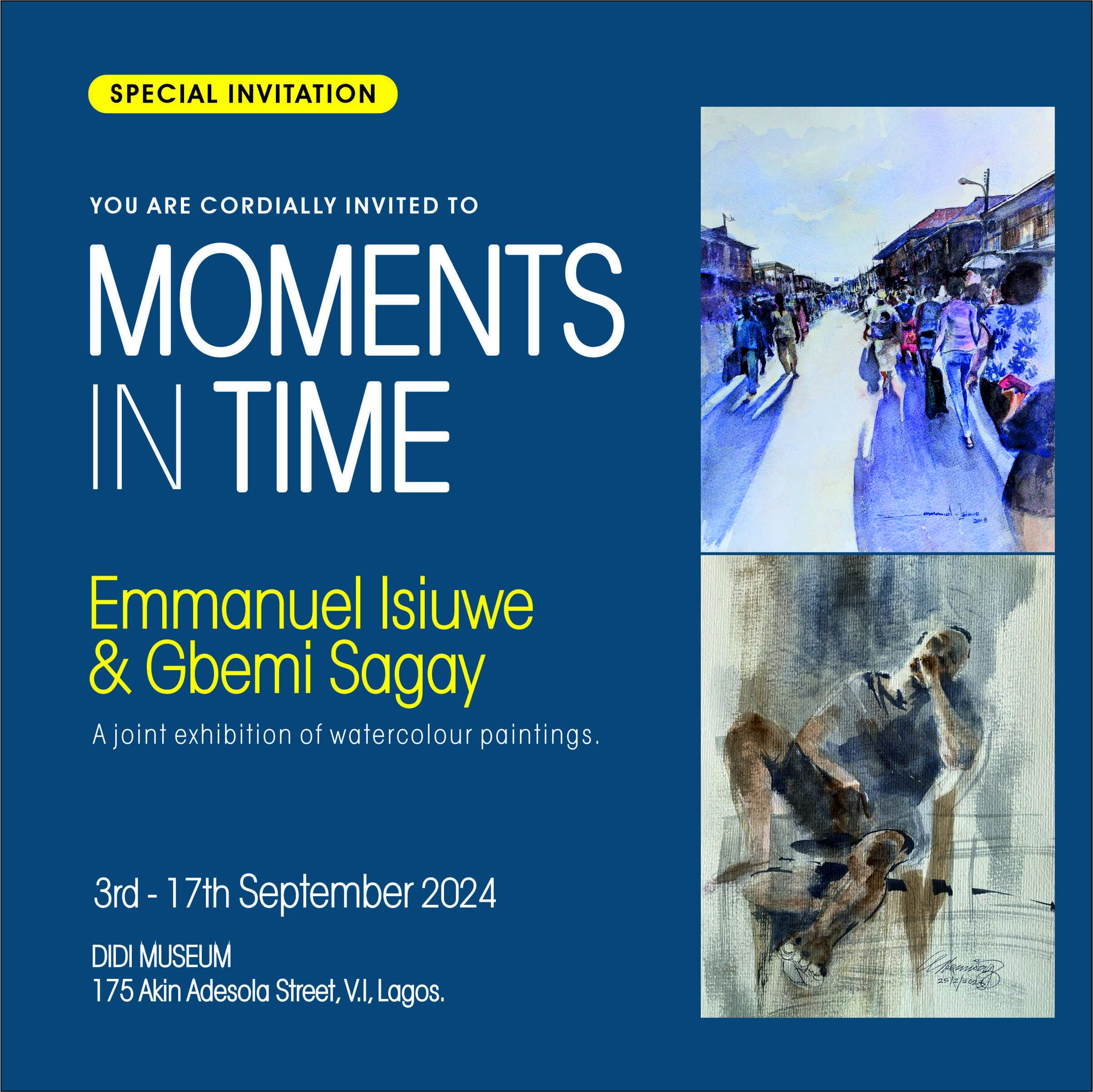

Moments in Time: A joint exhibition of watercolour paintings

Click to read...

Kunle Adeyemi Creative Art without Borders

Click to read...

Oghagbon Argungu series exhibition 10, 2024: Fieldnotes from a master

Click to read...

Metalphysics: Muraina Akeem's loud celebration

Click to read...

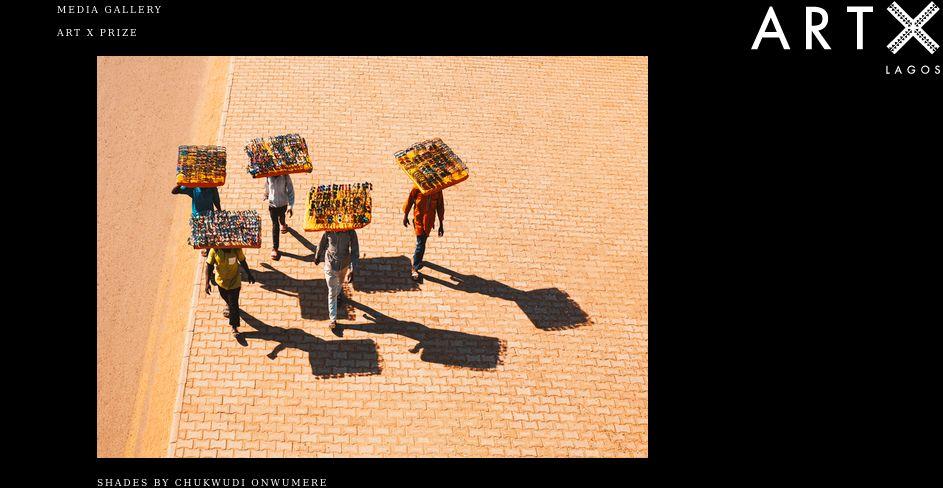

ART X Prize 2021 finalists announced

Click to read...

Art educators meet, counsel on best way to reposition visual arts in schools and the society

Click to read...

James Baldwin on the Artist’s Struggle for Integrity and How It Illuminates the Universal Experience of What It Means to Be Human

Click to read...

Fact File...Curatorial note by Ovie Omatsola

Click to read...

Page 1 of 12 [Next] [Last Page]